February 27, 2023

Changes are happening in academia that align with the ongoing changes of what defines research outputs. The term from healthcare, “knowledge translation” reflects this shift of what counts when sharing out research. Knowledge translation is defined as “a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve the health of Canadians, provide more effective health services and products and strengthen the health care system” (CIHR, 2016, para. 4). As we can see, one can substitute education for health and come to a similar statement for education: “a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve the [education] of Canadians, provide more effective [education] services and products and strengthen the [education] system” (ibid).

Within educational research, which is enfolded under the social sciences (Cooper & Rodway, 2018; Crain-Dorough & Elder, 2021) the discussion of knowledge translation continues to grow. With Canadian research funding agencies requiring a research dissemination plan (Cooper & Rodway, 2018) the well-accepted peer-reviewed journal articles and academic conference presentations make the foundation to these plans. But funders are now looking for a variety of dissemination practices, and research plans need to reflect the multiple choices that are available. To address these striving for alternative research outputs, a digital story and infographic display facets of a research project that I co-led at Athabasca University. These two artifacts speak to the research findings but as well contribute to the ongoing discussions related to knowledge translation, the research to practice gaps, and how a small group of researchers experienced characteristics of these gaps.

The IDEA Lab@Athabasca University

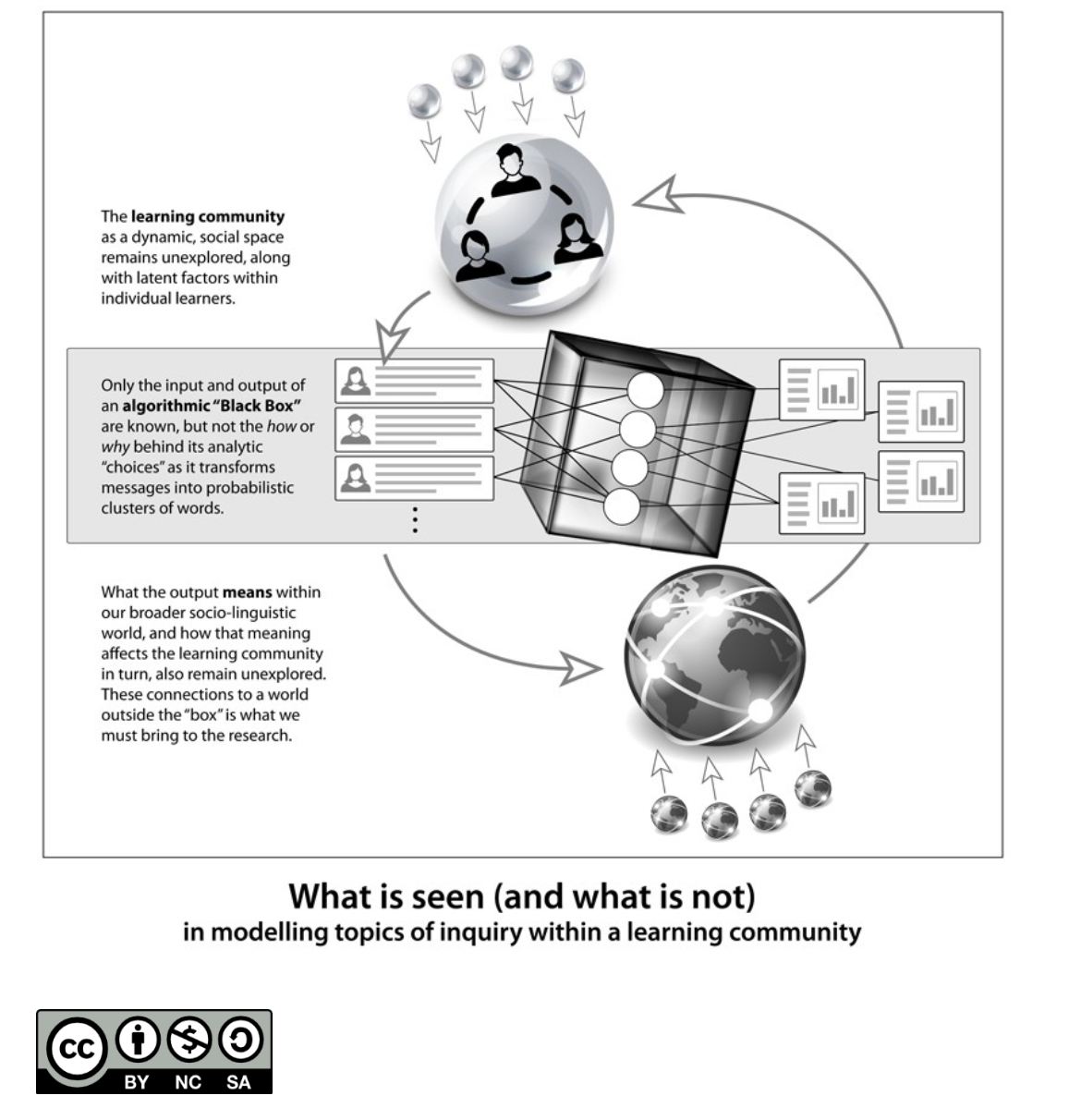

Cloud-computing tools are part of the innovative IDEA Lab launched at Athabasca University’s research office. My collaborators and I received funding and support to explore findings of our “Global Viewpoints on Open Educational Resources for Blended Learning” research project. This study applied the tools offered by data mining while examining Open Educational Resources (OER), openness in education through massive online open courses (MOOCs), and the perspectives of educators on the topic of using OER for blended learning. Data for analysis came from MOOCS that had been offered by Athabasca University and the Commonwealth of Learning through the Blended Learning Practice MOOC. Within this free, online course, participants respond to a discussion forum question about the role of OER within their teaching context. These forums, from six different offerings of this MOOC, formed the data sets for analysis using cloud-computing tools using Ronin, the research branch of Amazon Web Services. Using topic modelling analysis, we examined the impressions of MOOC participants with regards to OER as part of blended learning and teaching.

New to cloud-computing research

Our research team (Dr. Marti-Cleveland Innes, Dr. Elena Chudeva, and I) were novices to educational research using cloud-computing. Part of our reasoning in taking on this research, and in effect being learners again, was to understand through our decision-making and experiences what cloud-computing tools may mean for education research. With the onslaught of ed tech and online learning throughout all levels of education there is a flood of data – and data about the data is part of the future of education research. To keep abreast of change for our own learning and for the sake of our graduate students were two additional reasons to pursue this project.

As beginners to cloud-computing the Idea Lab members welcomed us because this is part of what the initiative is about. We were also part of the first cohort of researchers so there were many Idea Lab components being put together concomitantly with our MOOC research project. Because of this unknown terrain, the three of us had a range of thoughts, reactions, and emotions to the unfolding of our research and when the opportunity occurred to apply for further funding to support research dissemination efforts (i.e. Athabasca University’s faculty professional development fund), we opted to hire a graphic illustrator to create an infographic and a digital story about our findings and this unique to us research process.

Knowledge translation

The infographic has become a common research output in the sciences, similar in some ways to a poster. Because they are digital, infographics easily provide a visual and textual representation of key ideas. For research such as ours, they summarize points and convey information succinctly using images to deepen and extend information. Infographics may convey a process, statistics, or in our case, key concepts, with the images providing imaginal suggestions.

A digital story follows a story arc and provides facts and information. These elements are of course important factors within a digital story about the research process but using creative choices such as image selection, cropping, camera zooms, and a voice over of the person whose story it is to tell, a digital story may provide aspects of the backstage events of what occurred. Emotions, tensions, internal, and external dialogues – these are possible through the multi-modal intertwining that a digital story empowers and may fill in parts of the researching process.

In our OER research project, being learners of these tools was a place of growth, vulnerability, questioning, and mean-making. A digital story offered a means to express these experiences and an avenue to explore alternatives to research dissemination and knowledge translation. Additionally, both the infographic and digital story have creative commons licenses to align with the values of open education that inform Athabasca University, the mooc discussion forum topic and its participants, and the researchers’ beliefs.

The conventional knowledge translation outputs for this project have included presentations at conferences and academic papers. These outputs speak to the typical paths of sharing research within the research community. However, for this project we had the opportunity to explore additional means of sharing aspects of research insights and the research process involving cloud-computing. These two forms of knowledge translations widen our outputs; please see the infographic (Figure One) and click to watch our digital story, “A Story about Research in the Cloud”.

Final Thoughts

Whether researching with cloud-computing tools or multi-modal knowledge translations, education research will continue to iterate and innovate. Despite being uncertain about aspects of using topic modelling tools to explore the MOOC data we persevered and learned about the research decisions involved. We extended what we knew for ourselves as researchers and for graduate students. These changes to tools and knowledge translations are not disruptions to ignore but rather are opportunities for growth and critical reflections as individual researchers contributing to the ever-widening field of education.

The research project was supported by Athabasca University’s Research Office Idea Lab. The infographic and the digital story were supported by the Athabasca Professional Development Fund.

References

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). (2016, July). Knowledge Translation – About Us. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html

Cooper, A., & Rodway, J. (2018). Knowledge Mobilization Practices of Educational Researchers Across Canada. 48(1).

Crain-Dorough, M., & Elder, A. C. (2021). Absorptive Capacity as a Means of Understanding and Addressing the Disconnects Between Research and Practice. Review of Research in Education, 45(1), 67–100. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X21990614

Hollweck, T., Link to external site, this link will open in a new window, Netolicky, D. M., Link to external site, this link will open in a new window, Campbell, P., & Link to external site, this link will open in a new window. (2022). Defining and exploring pracademia: Identity, community, and engagement. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 7(1), 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-05-2021-0026

About the Contributor

Dr. Connie Blomgren is an Associate Professor in the Master of Education in Open, Digital and Distance Education at Athabasca University.

Except otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

From October 11-13, I was in Anaheim attending and presenting at the OpenEd 2017 conference. I met old friends and new. I collected business cards and learned from those I met in sessions or as I took a coffee break. Old connections and past experiences were renewed in unexpected ways – as well as making new connections and possibilities. This process of change and revisiting the old are part of being open…and of being part of the Open Educational Resources (OER) world and its larger affiliation with the open movement.

From October 11-13, I was in Anaheim attending and presenting at the OpenEd 2017 conference. I met old friends and new. I collected business cards and learned from those I met in sessions or as I took a coffee break. Old connections and past experiences were renewed in unexpected ways – as well as making new connections and possibilities. This process of change and revisiting the old are part of being open…and of being part of the Open Educational Resources (OER) world and its larger affiliation with the open movement. The opening keynote by Ryan Merkely – a fellow Canadian – amid this primarily American audience reinforced that OER ties to Creative Commons and that there will be a CC certificate offered in April 2018. He summarized how CC is working on 3 aspects – teaching, partnering and movement-building – as forming their current and near future focus. This concept of the significance of the commons was a theme further explored by the Friday morning keynote by David Bollier who encouraged us to reframe what OER means beyond the increasing drive to commodify content and to recognize that *open* is not the same as a commons. He asked – who IS taking care of open resources? And encouraged us to be mindful that a faux commons is possible i.e. we need to think of the Commons in more abstract terms.

The opening keynote by Ryan Merkely – a fellow Canadian – amid this primarily American audience reinforced that OER ties to Creative Commons and that there will be a CC certificate offered in April 2018. He summarized how CC is working on 3 aspects – teaching, partnering and movement-building – as forming their current and near future focus. This concept of the significance of the commons was a theme further explored by the Friday morning keynote by David Bollier who encouraged us to reframe what OER means beyond the increasing drive to commodify content and to recognize that *open* is not the same as a commons. He asked – who IS taking care of open resources? And encouraged us to be mindful that a faux commons is possible i.e. we need to think of the Commons in more abstract terms.